In the global catalog of unusual accolades, few are as culturally and biologically intriguing as Unusual Award N.13—an informal yet fascinating nod to the phenomenon of extreme gluteal proportions observed in some African women. Though this designation may seem odd or even reductive at first glance, its existence underscores a complex tapestry of anthropology, beauty norms, health, colonial history, and gender politics. What is the origin of this anatomical trait? Why has it been given special attention? And what does it tell us about the intersection of biology, environment, and cultural perception? – unusual award n.13: extreme gluteal proportions in african woman

This article delves into these questions and more, offering a detailed examination of extreme gluteal proportions not as a novelty, but as a significant point of conversation that traverses genetics, history, and evolving standards of beauty across continents. – unusual award n.13: extreme gluteal proportions in african woman

The Biological Basis of Gluteal Adiposity

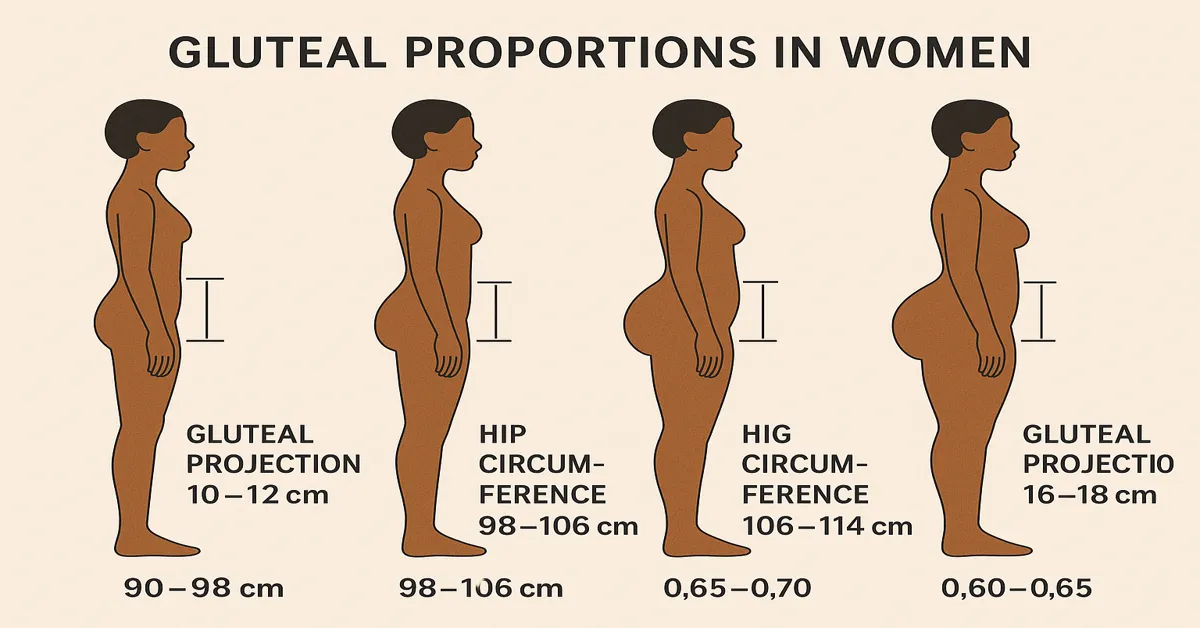

To understand the context of Unusual Award N.13, we must begin with the science. Gluteal adiposity—the accumulation of fat in the buttocks—is not unique to one population, but its extreme form has often been observed among women from specific sub-Saharan African ethnic groups. This trait is technically referred to as steatopygia. (unusual award n.13: extreme gluteal proportions in african woman)

Steatopygia is the pronounced development of fatty tissue over the buttocks and thighs, typically hereditary and most prominently seen in groups like the Khoisan people of southern Africa. Scientists believe that this trait evolved as a form of sexual dimorphism or as an adaptation to harsh environmental conditions—specifically, fat storage in regions of the body where it can be efficiently used during times of scarcity without impeding locomotion or thermoregulation.

Unlike visceral fat, which surrounds internal organs and is associated with a range of metabolic issues, gluteofemoral fat is largely subcutaneous and is, according to some studies, associated with lower cardiovascular risk and positive hormonal balances in women.

A Legacy of Misunderstanding: Colonial Gaze and Exoticization

The interest in extreme gluteal proportions has often strayed from scientific inquiry into the realm of spectacle—especially during the colonial period. Perhaps the most infamous example is Sarah Baartman, a Khoisan woman taken to Europe in the early 19th century and paraded around as the “Hottentot Venus.” Her body, particularly her large buttocks, became an object of both fascination and degradation. She was subjected to voyeurism, racial pseudoscience, and objectification.

Baartman’s story reflects a broader pattern of the colonial gaze—how European observers constructed narratives around African bodies to fit notions of the exotic and the “other.” These portrayals lingered for centuries, influencing not only Western perceptions of African women but also African perceptions of themselves under a post-colonial framework.

Reclaiming the Narrative: Modern Perspectives and Empowerment

In recent decades, African women and diasporic communities have worked to reclaim control over narratives that historically painted them in objectified or pathologized lights. The attention given to large gluteal proportions has shifted in tone, from spectacle to celebration, though not without complications.

In countries like South Africa, Nigeria, and Ghana, fuller figures are often seen as desirable and healthy—symbols of wealth, fertility, and femininity. Social media influencers and public figures, including celebrities with African heritage, have helped reframe gluteal adiposity not as something to be hidden or ashamed of, but as a symbol of identity and pride.

Still, this shift invites further dialogue. Is the celebration of such proportions always empowering? Or does it risk perpetuating a different kind of objectification—one wrapped in a new cultural aesthetic but still rooted in physical appraisal?

The Role of Genetics and Evolutionary Anthropology

Genetic studies have shed light on why certain populations exhibit traits like steatopygia. These studies suggest a polygenic basis for body fat distribution, influenced by both heredity and environmental pressures. For early human populations in sub-Saharan Africa, storing fat in the buttocks may have been adaptive—especially for women, who needed efficient energy reserves for reproduction and child-rearing in food-scarce environments.

Unlike abdominal fat, gluteofemoral fat doesn’t disrupt organ function. It is more resistant to breakdown and tends to be retained during lactation or periods of undernourishment—making it a critical evolutionary asset. In this light, what has been dubbed an “unusual award” is actually a fascinating example of natural selection and survival strategy.

Medical Considerations: Health Implications and Misconceptions

Contrary to harmful stereotypes, extreme gluteal proportions do not correlate with poor health. In fact, studies suggest that women with greater fat storage in the lower body tend to have a lower risk of metabolic diseases compared to those with central obesity (fat stored around the abdomen).

However, problems can arise when social pressure or beauty standards push women toward surgical or cosmetic enhancement, such as illegal silicone injections or unsafe procedures performed in unregulated clinics. These trends are not unique to Africa and can be seen globally, reflecting the complex interplay between body image, cultural norms, and health.

Cultural Interpretations: Symbolism in Tradition and Modernity

In many African communities, the body is not just a vessel—it is symbolic. Traditional dance, attire, and ceremonies often emphasize movements that celebrate the hips and buttocks. In some cases, coming-of-age ceremonies include rituals that symbolize or even emphasize gluteal fullness as a marker of maturity and beauty.

This cultural valorization contrasts sharply with Eurocentric ideals that have historically favored thinness. Yet, as the world becomes more interconnected, these lines are blurring. African aesthetics are influencing global fashion and beauty, even as Western media continues to export its own standards—sometimes creating cognitive dissonance among younger generations.

Popular Media and the Rise of the “Booty Economy”

The 21st century has seen the rise of what some have dubbed the “booty economy”—an industry fueled by the popularity of curvaceous bodies in music, media, and fashion. From hip-hop videos to reality TV, curvy figures—especially those with pronounced buttocks—have become aspirational for many.

Yet, the question remains: who benefits from this economy? While African women may find their natural bodies celebrated more in media, the commercial gains often flow toward brands, influencers, or industries that co-opt the aesthetic without crediting its cultural origins. Unusual Award N.13 thus reflects a broader irony: that traits once derided are now monetized, often by those outside the originating community.

Beyond the Award: Language, Labeling, and Responsibility

It is important to interrogate the framing of something like “Unusual Award N.13.” Who gets to define what is “unusual”? In what context? Labels carry power. They shape perception, policy, and even self-worth. While the title might be offered tongue-in-cheek or as a curiosity, it is imperative that discourse around it is informed, respectful, and nuanced.

Terms like “extreme” or “unusual” can stigmatize rather than illuminate. A more appropriate approach might be to treat such traits as variations of human anatomy—neither better nor worse, simply different and worthy of study and respect.

Education and Scientific Literacy: Reframing the Narrative

One of the most effective ways to counter reductive narratives is through education. Teaching the biological, cultural, and historical factors behind gluteal proportions can help foster a deeper understanding and appreciation.

Public health programs, anthropology curricula, and even media training can benefit from incorporating more accurate, sensitive portrayals of African body types. Science should not only answer “how” these traits evolved, but also “why” we’ve interpreted them in certain ways—and what those interpretations reveal about our collective psychology.

Toward a Global Dialogue: Body Positivity and Cultural Exchange

As global conversations around body image and beauty standards evolve, there is room for genuine exchange. African communities can contribute meaningfully to this discourse, offering insights into alternative ways of valuing the body—not just aesthetically, but holistically.

Rather than seeing Unusual Award N.13 as an oddity, we can view it as a catalyst for broader questions: What makes a body “normal”? Who sets the criteria? And how can we build societies where all body types are respected, not merely tolerated or exoticized?

Conclusion: From Object to Subject

In reassessing the meaning of extreme gluteal proportions through the lens of Unusual Award N.13, we find a mirror reflecting our deepest assumptions about race, gender, history, and beauty. What begins as an anatomical trait quickly unfolds into a much larger story—one of adaptation, colonial legacy, cultural pride, and ongoing struggle for representation.

African women with naturally full figures should not be reduced to spectacles or stereotypes. They are subjects of history, agents of culture, and embodiments of a human diversity that defies easy categorization. The unusual, it turns out, may simply be what we have yet to fully understand.

Click Here To Read More Stories!

FAQs

1. What is Unusual Award N.13, and is it an official designation?

Unusual Award N.13 is not an official scientific or governmental recognition. It’s an informal, often internet-circulated label that draws attention to the anatomical trait of extreme gluteal proportions observed in some African women. The term highlights public fascination but is often used without proper cultural or scientific context.

2. What causes extreme gluteal proportions in some African women?

This trait, known scientifically as steatopygia, is largely genetic and has evolved over time, particularly among certain ethnic groups like the Khoisan. It likely developed as a form of energy storage that helped with survival in arid climates. Hormonal and environmental factors may also play supporting roles.

3. Is this trait considered healthy or unhealthy?

Gluteofemoral fat—fat stored in the buttocks and thighs—is generally considered healthier than abdominal fat. It is associated with a lower risk of heart disease and diabetes, making it a positive from a metabolic health standpoint. However, societal pressure for exaggerated proportions can lead to unsafe cosmetic practices.

4. Why has this trait been historically objectified or exoticized?

Colonial-era pseudoscience and racial stereotyping played major roles in exoticizing African bodies. The most notorious case is Sarah Baartman, who was exhibited in Europe due to her pronounced buttocks. This objectification has had lasting effects on how African women’s bodies are perceived in media and society.

5. How is this trait viewed in modern African cultures?

In many African societies, fuller hips and buttocks are considered signs of beauty, fertility, and femininity. However, global beauty standards and media influence are changing perceptions, sometimes creating tension between traditional ideals and Westernized body expectations.